Why Music Education Builds the Skills AI Can’t Replace

At a major tech company, my friend Stewart often found himself in an unexpected role: adult project manager for adult professionals who never learned how to manage projects. “Nobody I work with knows how to practice,” he told me. “They just hope for inspiration before the deadline. I spend half my time explaining how to break something big into smaller pieces.”

Stewart is an innovator and inventor of AI-forward tech products now, but he trained as a classical pianist at Eastman Conservatory. He credits his intense music background with shaping the way he approaches complex tasks: backwards planning, structured iteration, deadline awareness, and mental stamina. What frustrates him isn’t that people lack technical skills—it’s that they lack scaffolding instincts. They don’t know how to think like musicians.

And they should know, because music education isn’t just artistic. It’s cognitive infrastructure.

What AI Can’t Do (Yet)

According to the World Economic Forum, the most valuable human skills in the age of automation are:

- Critical Thinking

- Creativity

- Emotional Intelligence

- Coordination with Others

Current AI limitations:

- Lacks context-awareness across time

- Struggles with ethical prioritization

- Cannot interpret subtle emotional cues

- Doesn’t know why a choice matters—just that it can generate one

What musicians do naturally:

- Manage complex systems in real time

- Interpret emotional subtext

- Adapt to changing inputs without losing the goal

- Bring coherence and pacing to layered, ambiguous work

Bottom line: AI can execute. Musicians can orchestrate.

Music Students Think Like Project Managers

Music students learn to work backward from performance goals. They don’t “cram” for concerts. They start months in advance, mapping out difficult passages, distributing their efforts, and logging progress. This is scaffolding. This is sprint planning.

They also learn how to sequence—what must happen first, what can be delayed, what needs extra time. They triage the way a team lead does when breaking a product into stages. Deadlines aren’t abstract motivators; they are structural endpoints. The concert date doesn’t change.

The Suzuki Method as Scaffolding in Action

Dr. Suzuki emphasized that every child can learn with the right environment, repetition, and modeling. But beneath the nurturing tone of Suzuki’s philosophy lies a methodical system that builds executive function from day one. Students don’t just play music—they follow a meticulously structured path: breaking down pieces into bite-sized tasks, mastering them slowly, and building fluency through repetition. Parents and teachers serve as project managers in the early stages, modeling how to approach big goals in small, manageable steps. Over time, the child internalizes that scaffolding. This is backwards planning in its purest form.

Suzuki’s relationship-based learning structure develops something AI tools can’t replicate: identity formation and emotional regulation through shared attention. A young student doesn’t just learn what to do—they learn how to be, by watching and absorbing the behavior of caregivers and teachers who model patience, persistence, and emotional steadiness. The triadic learning environment—child, parent, and teacher—cultivates co-regulation, which builds the foundation for lifelong self-regulation. No AI interface can attune to a student’s emotional state, slow down to match their internal pace, or offer the steady gaze that says, “I’m with you.”

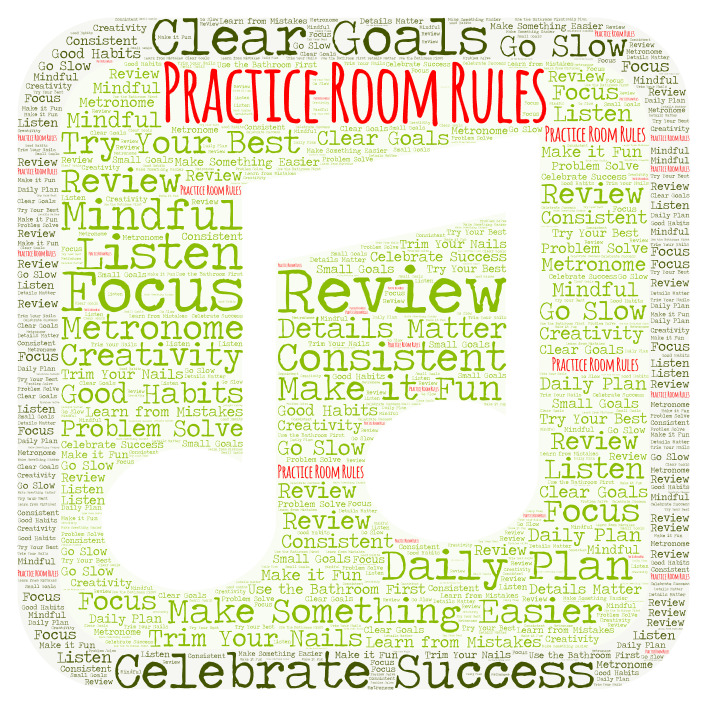

Even in repetition, the Suzuki method reaches depths AI cannot touch. An AI app may guide practice with reminders or track repetitions, but it can’t encourage meta-awareness. Suzuki students are taught to listen differently each time—to reflect, not just repeat. This productive repetition develops critical thinking and self-observation, skills that generalize beyond music into writing, problem-solving, and leadership. The review is intentional, reflective, and ever-evolving. AI can simulate correct output. Suzuki builds interpretive judgment.

Ultimately, AI can simulate learning tasks. It can prompt practice, score accuracy, even mimic feedback. But it does not shape character. It cannot build the slow, layered identity of a self-led learner. Suzuki education is not about checking boxes—it’s about becoming someone who knows how to learn.

Feedback, Focus, and Failure Tolerance

A musician is trained to fail, adjust, and repeat. They listen for micro-errors in phrasing or rhythm and revise accordingly. This feedback loop is internalized from a young age: detect the problem, isolate it, fix it, reinforce the fix, and build from there.

Contrast this with many professionals who view feedback as critique or confrontation. In music, feedback is fuel. The rigor of deliberate practice teaches resilience, self-correction, and iterative patience—all core skills in any demanding profession. This aligns with Anders Ericsson’s research on deliberate practice, which shows that expertise develops not from repetition alone, but from targeted feedback and gradual refinement.

Music also cultivates deep work capacity: hours spent in focused, distraction-free refinement. Psychologist Angela Duckworth found that musicians tend to score higher on measures of grit and perseverance—traits deeply connected to long-term success in any field. In an attention-fractured world, that alone is a competitive advantage.

Suzuki = Scaffold

What makes the Suzuki Method uniquely powerful for future-ready thinking?

- Repetition with intention – Builds cognitive endurance and pattern recognition.

- Layered complexity – Early pieces teach foundational patterns that scaffold advanced ones.

- Parental modeling – External executive function becomes internalized over time.

- Goal chunking – Each piece is broken into digestible sections and skills.

- Long-term structure – Review is built in, not tacked on.

Suzuki doesn’t just teach music. It builds a brain that can plan, adapt, and persist—skills automation can’t replace.

Ensemble Empathy & Adaptive Listening

Playing in an ensemble requires responsive coordination. You must critically listen and respond to both yourself and others. You have to sense when a colleague is rushing, when a dynamic shift is needed, when a cue is coming. This is collaborative awareness, practiced in real time.

Teamwork in music demands emotional regulation under pressure, quick recovery from mistakes, and a kind of ego-balancing that many workplaces struggle to teach. These habits are not abstract; they are built, breath by breath, in practice rooms and rehearsal spaces.

The AI Angle: Humans Still Have to Orchestrate

As AI accelerates, it replaces many routine tasks—but not meta-cognition. AI can generate an email, write code, and draft a chart. However, it can’t reliably determine which problem to solve, which approach is meaningful, or how to synthesize ambiguity into clarity.

Current AI systems lack intentionality, ethical reasoning, and interpretive nuance. They cannot prioritize tasks based on long-term context, nor can they adapt strategies in real time based on subtle human cues. AI tools can assist in execution, but they need human guidance to set goals, adjust course, and define value.

This is precisely the domain of musically-trained minds: people who are accustomed to navigating layered goals, managing emotional texture, coordinating with others, and iterating toward excellence. Musicians are used to asking: What matters here? How do we pace this? Where should the emphasis fall?

According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report, the most valuable human job skills in the AI era include critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, and coordination. These are precisely the skills cultivated in ensemble rehearsal and solo practice alike.

That’s where music-trained minds excel. They’re used to navigating complexity, choosing interpretive direction, managing time constraints, and adjusting to real-world variables in real-time. They bring structure to chaos. AI needs conductors.

Musicians in Tech

Brandon Tory is a senior engineer at Google who also happens to be a rapper, songwriter, and record producer. His music career sharpened his sense of timing, pattern, and narrative structure—skills he now uses to build artificial intelligence systems.

Zakariyya Scavotto, a classical pianist turned machine learning researcher, works on AI transparency and neural engineering. His music training gave him an edge in pattern analysis and systems thinking.

Evolone Layne, president of the Google Student Developers Club at Howard University, began her path as a vocal student. Today she leads major tech projects and credits her early musical training for her leadership instincts and creative focus.

These are not exceptions. They are proof points.

Music creates minds that know how to think, structure, and lead.

Stewart’s Real-World Proof

Stewart’s job title doesn’t include “conductor,” but it might as well. He conducts timelines, workflows, and overwhelmed colleagues. He organizes ambiguity into sequence, deadline, and momentum. All of that came from piano.

He tells me he sometimes wishes his team had been through a conservatory—not for the music, but for the habits. The systems thinking. The urgency. The quiet confidence that comes from knowing you can logically break something down, piece by piece, until it works and is a thing of beauty.

Closing

Music students don’t just learn music. They learn to lead, to listen, to persist, and to plan. In a world where machines are gaining fluency in output, the humans who thrive will be the ones who know how to structure the process. And music is still one of the best teachers we have.

If you want to future-proof a child’s education—or your own workforce’s capacity to think—start with music. Not for the concert, but for the cognitive rehearsal it builds every day.

References and further reading

- Ericsson, K. Anders, Ralf Th. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Römer. “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance.” Psychological Review 100, no. 3 (1993): 363–406.

- Duckworth, Angela L., Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews, and Dennis R. Kelly. “Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92, no. 6 (2007): 1087–1101.

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023.

- Harvard Medical School. “Music and the Brain.” Harvard Neurobiology Department. Accessed May 2025. https://neuro.hms.harvard.edu/research/music-and-brain.

- NAMM Foundation. “The Benefits of Music Education.” Accessed May 2025. https://www.nammfoundation.org/articles/2014-06-01/benefits-music-education